A widely held belief by labour-relations practitioners is that a union or employer can influence its likelihood of success at grievance arbitration via arbitrator selection. That is to say, practitioners believe that arbitrators have observable, stable, and significant decision tendencies that affect their chances of winning an arbitration. That’s not to say that facts, evidence, and jurisprudence don’t matter. But a party rarely has much control over these factors (i.e., you have the case you have). What is within a party’s control (more or less) is who hears the case.

“Who you get affects what you get” is an interesting conjecture that, if true, could suggests strategies for parties to adopt to increase their odds of success. Taking this conjecture as starting point, a colleague and I have been working to test whether or not arbitrators have observable, stable, and significant decision tendencies that can be used to predict future decisions. This is a conceptually and methodologically challenging project and I thought thinking aloud about this project might be of interest to SOSC 366 and IDRL 316 students (as well as a useful process of metacognition for me).

Our underlying approach is rooted in social constructivism. This theory, loosely speaking, asserts that there is infinite stimuli in the world. What stimuli we pay attention to and how we interpret those stimuli is shaped by our experiences, values, and beliefs. In this way, we socially construct our world. For example, bosses often frame conflict with workers as rooted in a communication or attitude problem rather than as an expression of conflicting interests.

Social constructivism is, I think, a reasonable starting point for analyzing arbitration decisions. Arbitrators are normally tasked with making complex decisions, often by sifting and weighing evidence and arguments and applying principles and precepts to come to decisions about what has happened and what ought to happen. This kind of work entails exercising significant judgment about what information is important and what it means. While arbitrators carefully apply many useful conventions and tests when making these decisions (e.g., around witness credibility), social constructivism assumes that arbitrators are ultimately relying upon their experiences, values, and beliefs (more on this below) when exercising their judgment.

This approach suggests, to the degree that arbitrators have, among themselves, different experiences, values, and beliefs, they might come to different conclusions in a case when faced with the same information. (There is some research that concludes (1) arbitrators are consistent in the factors they consider their decisions over time, and (2) different arbitrators can come to very different conclusions when deciding identical cases. This research broadly accords with the social constructivist approach we've adopted.)

The nature of grievance arbitration makes it hard to test the “who you get affects what you get” conjecture. Facts, evidence, and jurisprudence clearly affect individual decisions in important ways. The unique nature of each case impedes direct comparisons of decisions rendered by different arbitrators. And, to the degree that social constructivism occurs outside of our awareness, its operation may be difficult to see in arbitration decisions (although I do acknowledge how arbitrators carefully walk readers through the facts and arguments, and their analyses).

A different approach to testing this conjecture (and the one we've settled on) is to look at patterns in arbitrator decision-making over a large number of cases. The idea here is that the unique facts of each case (which will sometimes favour the employer and sometimes the union) will “average out” over a large enough number of cases (>1000 at this point) to create a baseline of wins and losses. Once the dataset is coded, we can then assess:

- whether there are significant differences in the win-loss ratios (i.e., decision tendencies) among arbitrators and compared to the baseline,

- how stable these decision tendencies are over time, and

- the degree to which these tendencies are usefully predictive of future decisions.

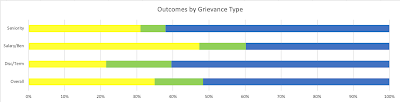

I’ve read and coded over 700 awards in the past year or so. The patterns we saw early in the analysis (such as those reported

here) continue to hold true. The raw win-loss ratio data is quite stark and, at times, eyebrow raising. This suggests that the “who you get affects what you get” conjecture may have some merit in the sense that some arbitrators seem to have clear tendencies which may make them, from an outcomes perspective, more (or less) desirable as adjudicators for specific cases.

We’ll need to wait until I finish coding all of the awards/decisions before we move onto testing the degree to which past decision tendencies can predict future decisions. That will involve (I think) segregating decision data into two groups for each arbitrator (maybe two thirds as a predictor pool and one third as a test pool) and assessing the degree to which we can, knowing an arbitrator’s win-loss ratio in the predictor pool, predict the outcomes of arbitrations in the test pool. (Obviously, there are many complexities to control for in the analyses, such as differences on which side bears the initial onus of proof and such).

Perhaps the biggest potential critique of this research is the premise that arbitrators’ values, beliefs, and decisions play a meaningful enough role in the outcome of decisions to warrant paying attention to them. You could very reasonably take the position that the impact (if any) of social constructivism would be rendered irrelevant because of the importance of the facts of each case plus the careful decision-making process that arbitrators routinely exhibit.

This view accords with the widely (but not universally) held belief that adjudicators (e.g., judges) are for the most part, neutral actors who are unlikely to be systematically biased in one direction or another. If we set aside, for the moment, that labour-relations practitioners, who have extensive experience with adjudicators, don’t believe this to be true, it is fair to ask if there any evidence that arbitrator bias operates in important ways? (We’re also setting aside the broader literature on bias in other forms of adjudication).

I’ve been keeping a diary of observations during coding. One of the striking things is how few of the 700+ decisions I’ve read where I got to the end and went “yeah, the arbitrator totally blew that call”. I’ve only run across (I think) one case so far where I’ve thought the decision was just clearly wrongheaded. In all of the other cases, the decision (based on the analysis presented by the arbitrator) was plausible (even if, maybe, I might have made a different decision). I don’t know if that pattern reflects that (1) arbitrators are good at getting to a sensible decision, (2) arbitrators are good at writing reasons that justify the decision they’ve reached, or (3) both.

I went back and forth about whether to link to the “you blew it” decision and, in the end, decided not to. There is no reason to dog pile on an arbitrator who made a decision in a complicated case with some ambiguous facts and whose other decisions seem generally fair minded. I mention the case only because it illustrates how an arbitrator’s values, beliefs, and expectations can shape the decision. It is a bit hard to explain this without going into identifying details of the case so you'll have to trust me a bit here.

The case revolved around an assault in the workplace and the worker defending themselves. There was clear and uncontested evidence that the worker had to and had cause to defend themselves: they were assaulted, put in a headlock, and feared for their safety. The arbitrator discounted this evidence and instead blamed the worker for triggering the assault because the worker was inattentive to the assailant’s needs. The arbitrator used the circumstances of the assault (e.g., a vulnerable assailant, moderately ambiguous and inconsistent evidence) to conclude that the worker’s termination was justified. The subsequent dissent by the union representative on the panel was, at the risk of understatement, pretty sharp.

An award that is not plausible is a pretty surprising outcome. Awards are designed to require arbitrators to clearly justify their decisions. This structural feature of awards ought to preclude decisions that clearly reveal arbitrator bias in interpretation of the evidence and drawing conclusions. Basically, the decision ought to be at least plausible on the face of it (and the vast majority are). That we have an example where the arbitrator’s reasoning is just not plausible runs contrary to the purpose of the system, which is to preclude both the fact and appearance of bias.

This is, certainly, just a single case and, Lord Vader knows, I’ve had off days myself. I think the point of it is that this decision is evidence, independent of the views of labour-relations practitioners, that arbitrator bias can occur. (I suspect most often it is harder to detect because the impact of an arbitrator’s values, beliefs, and experiences are less obvious, perhaps being less stark and profound or better obscured by the procedural narrative.

In any event, this case combined with the widespread belief of labour practitioners supports, however tentatively, inquiring into whether arbitrator’s values, beliefs, and decisions play a meaningful enough role in the outcome of decisions using a social constructivist frame. Basically, there’s some smoke here; let's see if there is also fire.

Anyhow, I hope that was an interesting view into how a researcher thinks about research questions before and during the process of collecting and coding data.

-- Bob Barnetson