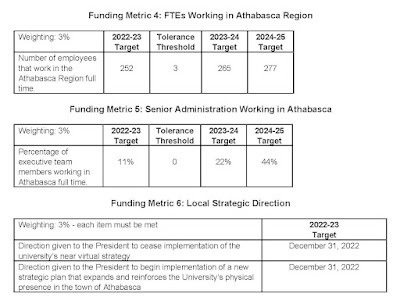

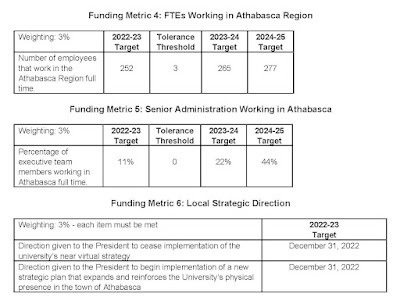

I have not yet seen a copy of the IMA (they are usually posted on institutional websites) but there have been announcements by the government and by AU President Peter Scott. The image below (which is apparently a copy of some of the performance-based funding metrics AU has agreed to as part of the IMA) has also been circulated on Facebook (sorry about the low quality).

Update 2022.12.14: The IMA is available here.

A few observations are helpful to understand this image:

On the issue of jobs in Athabasca, we have:

Specifically, I might be asking why the minister agreed to such a modest IMA. Did the minister really understand the implications of what he was signing? And, if so, why did he give AU a way to simply rag the puck on the jobs issue for another two years?

One explanation might be that the Minister got dumped into this fight by former Premier Kenney, who championed the jobs issue when we have trying to collect enough votes to keep his job last spring (and, when he didn’t, continued to fight to punish those who defied him) and the Minister (or the new Premier) just wanted a way out without losing too much face. So maybe he talks tough, signs a weak deal, declares victory, and move on? Alternately, maybe the Minister and his handpicked group of Board members got sold some snake-oil by some savvy eggheads. We’ll probably never know.

Whether the community can sustain its efforts to secure AU jobs in Athabasca in the face of an apparent (albeit possibly hollow) victory is hard to say.

Returning to the question of the Minister, one of the tidbits I’ve heard over the last few days is that some actors within the UCP are hoping to have “a better candidate” get the UCP nomination in the Minister’s riding of Calgary-Bow for the 2023 election.

I have absolutely zero insight into UCP politics. But it would be pretty funny if the ”better candidate” turned out to be current AU board chair Bryon Nelson. Nelson ran in the 2016 Progressive Conservative leadership race that was eventually won by Kenney as part of his plan to Frankenstein together a conservative party to beat the NDs.

-- Bob Barnetson

A few observations are helpful to understand this image:

- Metric 4 requires AU to have 252 staff working in the Athabasca region full-time by March 2023. A few caveats are warranted. This metric does not require staff to (1) work on campus, (2) live in the area, or (3) define how “working in the Athabasca region full-time” will be assessed (this may be set out in a document to which I don’t have access). I am told 252 is the present staff count, so no action by AU is immediately required. Note that there is a tolerance of 3 in the first year, so AU can actually reduce the number of staff working in the region in year one. By March 2025, AU has to increase the number by 25 full-time staff. A net 10% increase over three years is a very modest target, representing a shift of about 2% of AU’s 1200ish workers.

- Metric 5 requires AU to have 44% of its 9-member executive team working in Athabasca by March of 2025. The same caveats as above apply, which we can add that it is not clear (4) if these 4 can count towards the Metric 4 goal of 25, and (5) who defines a member of the executive. The university’s website list of executive members includes the presidents’ chief of staff (who already lives in town) and executive assistant but omits 3 VPs (1 in Calgary and 2 in BC). This list looks like an effort to game this metric by excluding people who perform actual executive functions and pad out the exec with people who don’t.

- Metric 6 requires the Board, by December 31, to direct the president to cease implementation of the near-virtual strategy and implement a new strategic plan that expands the university’s physical presence in the town of Athabasca. A couple of thoughts occur to me: (1) the near virtual plan will be fully implemented by the end of December so directing the president to “cease implementation” at that point is meaningless, and (2) expanding the physical presence doesn’t necessarily mean more jobs being located in town. AU is telegraphing some kind of research centre located in Athabasca, which would likely meet this requirement regardless if anyone ever uses it.

- A portion of AU’s government funding (rising eventually to 40%, last I heard) is contingent upon AU meeting these metrics. The 3% in the top left corner of metrics 4, 5, and 6 is the weighting they are given in the funding calculation. Update 2022.12.14: The 3% refers to the percentage of overall government funding at risk with this metric. So, if AU gets $47m of its $160m in revenue from that government and 15% of that $47m ($7.5m) is at risk in 20223/23, missing either of location-based targets (worth 3% each) would potentially institutions the $1.41m. But, apparently, the location-based targets don't operate until 2023/24 t. So the financial incentive tied to meeting these very modest metrics is pretty weak.

On the issue of jobs in Athabasca, we have:

- modest, ill-defined, and easily gamed jobs targets,

- that require no immediate action,

- backed by modest penalties,

- that will not take effect until long after the next provincial election,

- when there will be a different minister (more on that below), and

- likely a different government, which may re-negotiate or just dump performance-based funding and the associated metrics all together.

Specifically, I might be asking why the minister agreed to such a modest IMA. Did the minister really understand the implications of what he was signing? And, if so, why did he give AU a way to simply rag the puck on the jobs issue for another two years?

One explanation might be that the Minister got dumped into this fight by former Premier Kenney, who championed the jobs issue when we have trying to collect enough votes to keep his job last spring (and, when he didn’t, continued to fight to punish those who defied him) and the Minister (or the new Premier) just wanted a way out without losing too much face. So maybe he talks tough, signs a weak deal, declares victory, and move on? Alternately, maybe the Minister and his handpicked group of Board members got sold some snake-oil by some savvy eggheads. We’ll probably never know.

Whether the community can sustain its efforts to secure AU jobs in Athabasca in the face of an apparent (albeit possibly hollow) victory is hard to say.

Returning to the question of the Minister, one of the tidbits I’ve heard over the last few days is that some actors within the UCP are hoping to have “a better candidate” get the UCP nomination in the Minister’s riding of Calgary-Bow for the 2023 election.

I have absolutely zero insight into UCP politics. But it would be pretty funny if the ”better candidate” turned out to be current AU board chair Bryon Nelson. Nelson ran in the 2016 Progressive Conservative leadership race that was eventually won by Kenney as part of his plan to Frankenstein together a conservative party to beat the NDs.

-- Bob Barnetson