Earlier this week, the Parkland Institute released a report that I contributed to, entitled Thumb on the scale: Alberta government interference in public-sector bargaining.

This report examines how, in a time when workers’ Charter-protected associational rights appear to be expanding, the rate at which governments interfere with collective bargaining has skyrocketed.

It specifically looks at Alberta’s ongoing use of secret bargaining mandates, which turn public-sector bargaining into a hollow and fettered process.

This report is relevant because both UNA and AUPE have exchanged opening proposals with the government in the last few weeks and will be bargaining against secret mandates. The government opener in both cases was, unsurprisingly, identical and there is a huge gap between what workers are asking for and what the government is offering.

-- Bob Barnetson

Examining contemporary issues in employment, labour relations and workplace injury in Alberta.

Showing posts with label IDRL320. Show all posts

Showing posts with label IDRL320. Show all posts

Friday, February 23, 2024

Monday, November 20, 2023

Bill 5 continues government interference in collective bargaining

Canada has a long tradition of governments using their power as legislators to give themselves a further advantage in their role as an employer. This is called permanent exceptionalism. Basically, governments pass laws undermining public-sector workers’ bargaining power, justifying them as temporary and exceptional interventions, except they are neither.

My colleagues Jason Foster and Susan Cake and I published a study of legislative interventions in labour relations from 2000 to 2020 in a recent issue of the Canadian Labour & Employment Law Journal (vol 25, issue 1) called “Catch me if you can”: Changing forms of permanent exceptionalism in response to Charter jurisprudence.”

The upshot is that, during a time when the Supreme Court was finding that workers’ associational rights in the Charter included the right to collectively bargain and strike free from substantial interference, the rate of government interference significantly increased (tripling over the 1990s). Basically, governments have become addicted to rigging the game against public-sector workers.

Back in 2019, Alberta’s UCP government passed the Public Sector Employers Act. The PSEA allowed the government to give public-sector employers secret and binding bargaining mandates. This made the 2020 round of public-sector bargaining a hollow and fettered process (our study about this is currently in review) and let the government drive home a combination of wage freezes, miserly wage increases, and other rollbacks. This built upon a similar strategy use by the NDP government in the 2017 round of bargaining that also delivered several years of wage freezes.

Presently, the legislature is debating Bill 5, which amends the PSEA. The headlines around this Act have focused on how the government will be better able to attract certain types of public-sector workers (i.e., wages are too low) while also now controlling the wages for non-unionized workers via secret bargaining directives. In the house, the NDP is flagging how Bill 5 opens the door to pork-barrelling for public-sector CEOs.

Almost no one is examining how Bill 5 extends the original secret mandate powers. The new bill allows the government to create employer committees and associations to coordinate (and perhaps perform) bargaining, potentially on sector-wide bases. This is pretty much how it works at the big tables in education, health-care, and the core civil service now.

But, for the 250-odd bargaining tables among agencies, boards, and commissions, these amendments would allow for big changes. In theory, employers could bargain cooperatively against dozens and dozens of disparate small unions and union locals, each bargaining on their own. Combined with an inflexible government mandate, this would make it very hard for these workers to get a decent deal and would make it much easier for the government (via these employers) to drive further concessions into these contracts. There are no similar provisions for sectoral bargaining arrangements for workers.

Alberta is already suffering from significant staffing shortages in health-care and education. Further grinding wages and hollowing out of public sector-bargaining (combined with the government threatening to take control of Albertan’s Canada Pension Plan contributions and its efforts to grab up public-sector pensions) will make Alberta an unattractive place for new graduates to stay.

-- Bob Barnetson

Labels:

collective bargaining,

IDRL215,

IDRL309,

IDRL316,

IDRL320,

labour relations,

public policy,

unions

Tuesday, October 17, 2023

John Oliver on Union Busting

A friend sent me this clip of John Oliver exploring union busting in the United States.

Very applicable to Canada as well.

-- Bob Barnetson

Labels:

class,

collective bargaining,

HIST336,

IDRL215,

IDRL316,

IDRL320,

labour relations,

LBST200,

political economy,

strikes,

unions,

videos

Monday, July 24, 2023

Hollywood strikes highlight undercurrent of violence in labour relations

Two strikes, one affecting writers and the other actors, have brought most Hollywood productions to a stand-still over the past two months.

You can read a summary here but the gist is major studios are trying to cheapen work in order to gain a greater portion of the surplus value generated by labour.

The bosses’ strategy, at least with respect to the Writers Guild of America, appears to be simply starving out the workers. According to Vanity Fair, the bosses expect writers to run out of money by October and, once the workers are facing homelessness, they will resume negotiations and press for concessions. Starving workers until they give up is an age-old employer tactic.

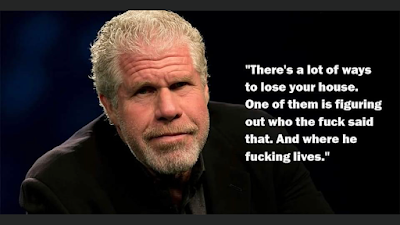

Actor Ron Perlman, in a now deleted video, reacted to the bosses’ plan this way:

That hasn't always been true, though. Underlying every job action is the potential for violence. Often it has been used by bosses to bust a strike. But, occasionally, workers will destroy the bosses’ property or attack them directly. The post-war labour compromise in Canada has attenuated this risk, in part by strictly regulating strikes and strike behaviour.

But, when the bosses refuse to negotiate in good faith (or the system looks otherwise completely rigged against them), worker commitment to obeying labour law may fray because it is no longer in their interest to do so.

We most often see this dynamic play out in wildcat strikes. But worker frustration doesn’t have to be channelled in that direction. A worker or smnall group of workers could, as Perlman hints, just destroy a boss’s house or yacht or factory or mine or whatever.

It is worthwhile for both bosses and workers to pay attention to the potential for this kind of behaviour as they strategize how to bargain. Bosses who decide to play hardball, may be opening Pandora’s box. And worker may be overlooking a significant source of leverage by discounting alternatives to picketing.

-- Bob Barnetson

The bosses’ strategy, at least with respect to the Writers Guild of America, appears to be simply starving out the workers. According to Vanity Fair, the bosses expect writers to run out of money by October and, once the workers are facing homelessness, they will resume negotiations and press for concessions. Starving workers until they give up is an age-old employer tactic.

Actor Ron Perlman, in a now deleted video, reacted to the bosses’ plan this way:

The motherfucker who said we’re gonna keep this thing going until people start losing their houses and apartments — listen to me motherfucker.

There’s a lot of ways to lose your house. Some of it is financial. Some of it is karma. And some of it is just figuring out who the fuck said that — and we know who said that — and where he fucking lives.Perlman’s statement got quite a lot of media play because it is out of step with most people’s understanding of how contemporary strikes play out (basically people stop working and walk around with signs until the boss decides to negotiate). Suggesting that bosses might face violent, real-world consequences for trying to get even richer by economically destroying workers’ lives is pretty uncommon these days.

There’s a lot of ways to lose your house. You wish that on people? You wish that families starve while you’re making 27 fucking million dollars a year for creating nothing? Be careful motherfucker. Be really careful. Because that’s the kinda shit that stirs shit up.

That hasn't always been true, though. Underlying every job action is the potential for violence. Often it has been used by bosses to bust a strike. But, occasionally, workers will destroy the bosses’ property or attack them directly. The post-war labour compromise in Canada has attenuated this risk, in part by strictly regulating strikes and strike behaviour.

But, when the bosses refuse to negotiate in good faith (or the system looks otherwise completely rigged against them), worker commitment to obeying labour law may fray because it is no longer in their interest to do so.

We most often see this dynamic play out in wildcat strikes. But worker frustration doesn’t have to be channelled in that direction. A worker or smnall group of workers could, as Perlman hints, just destroy a boss’s house or yacht or factory or mine or whatever.

It is worthwhile for both bosses and workers to pay attention to the potential for this kind of behaviour as they strategize how to bargain. Bosses who decide to play hardball, may be opening Pandora’s box. And worker may be overlooking a significant source of leverage by discounting alternatives to picketing.

-- Bob Barnetson

Labels:

collective bargaining,

HIST336,

IDRL215,

IDRL316,

IDRL320,

labour relations,

picketing,

political economy,

safety,

strikes,

unions

Wednesday, May 17, 2023

Reflections on Unifor's strategy during Regina's Refinery strike

Andrew Stevens and Doug Nesbitt recently published an article entitled “Refinery town in the petrostate: organized labour confronts the oil patch in Western Canada" (this article does not yet appear to be open access). This piece examines the lengthy strike and lockout at the Co-op refinery in Regina in 2019 and explores three main themes.

First, it examines how the union’s long-term approach to bargaining (which the authors term conciliatory and cooperative) left the union unprepared to cope with an aggressive employer intent upon driving major concessions into the union’s agreement (this is likely an important finding or many unions…). This included taking significant steps (e.g., building a camp to house a scab workforce) to ensure that a lockout of workers would be successful.

Second, it explores how the state and employers colluded to limit the union’s ability to effectively apply pressure on the employer through traditional and legal means (e.g., striking, picketing) through court injunctions and demands that workers’ picketing behaviour be treated as criminal. Allied employers also began demanding further legal constraint of picketing activity.

Third, the paper examines the effectiveness of civil disobedience and building solidarity networks to apply pressure to the employer in the face of collusion between the state and the employer and profound anti-union sentiment. The state’s response to union tactics that infringed upon the employer’s property rights included imprisoning union leaders and demonizing the union as an outsider. Of particular interest in the article is the analysis of how community support for the oil and gas industry benefitted the employer’s efforts to grind the compensation of workers.

The authors suggest that a more thoughtful approach to community engagement an the deployment of civil disobedience tactics by the union might shift the terrain of future disputes and increase the union’s leverage.

-- Bob Barnetson

First, it examines how the union’s long-term approach to bargaining (which the authors term conciliatory and cooperative) left the union unprepared to cope with an aggressive employer intent upon driving major concessions into the union’s agreement (this is likely an important finding or many unions…). This included taking significant steps (e.g., building a camp to house a scab workforce) to ensure that a lockout of workers would be successful.

Second, it explores how the state and employers colluded to limit the union’s ability to effectively apply pressure on the employer through traditional and legal means (e.g., striking, picketing) through court injunctions and demands that workers’ picketing behaviour be treated as criminal. Allied employers also began demanding further legal constraint of picketing activity.

Third, the paper examines the effectiveness of civil disobedience and building solidarity networks to apply pressure to the employer in the face of collusion between the state and the employer and profound anti-union sentiment. The state’s response to union tactics that infringed upon the employer’s property rights included imprisoning union leaders and demonizing the union as an outsider. Of particular interest in the article is the analysis of how community support for the oil and gas industry benefitted the employer’s efforts to grind the compensation of workers.

The authors suggest that a more thoughtful approach to community engagement an the deployment of civil disobedience tactics by the union might shift the terrain of future disputes and increase the union’s leverage.

-- Bob Barnetson

Labels:

collective bargaining,

government,

IDRL215,

IDRL309,

IDRL320,

labour relations,

picketing,

research,

strikes,

unions

Wednesday, May 10, 2023

UCP's record on labour issues

Alberta Views recent published an article I wrote about the UCP's record on labour issues. The article reprises and extends a chapter I wrote with Susan Cake and Jason Foster in a new book entitled Anger and Angst: Jason Kenney's Legacy and Alberta's Right (which is also worth a look).

The nub is basically that UCP labour policy can be best understood as an effort to shift the cost of labour from employers to workers by grinding wages and working conditions. The effect, particularly on and in Alberta's public-sector has been significant. Since the Alberta View's article is open access, I'll leave it for you to read more if you like.

-- Bob Barnetson

Labels:

employment standards,

government,

HRMT322,

HRMT323,

IDRL215,

IDRL308,

IDRL320,

labour relations,

LBST330,

political economy,

public policy,

research,

unions,

wages,

WCB

Wednesday, April 19, 2023

Podcast: Vriend 25 Years On

The Well Endowed Podcast is publishing a series on the 25th Anniversary of the Vriend decision. While sexual orientation had been deemed an analogous ground under s.15 of the Charter, Alberta had refused to include sexual orientation as a prohibited ground in its human rights legislation. This permitted discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation by private actors. In Vriend, the Supreme Court found that this exclusion offended the Charter and should be read into human rights legislation.

Vriend was ground-breaking litigation and this multi-part podcast begins by examining how Canada and Alberta treated members of the LGBTQ2+ community in the decades leading up to 1991 (when Vriend was fire by an Alberta college because of his sexual orientation). The degree of discrimination faced by the LGBTQ2+ detailed in the first episode is, frankly, shocking.

This decision has had significant impacts for labour relations, including the Charter, human rights, immigration, and sex work.

-- Bob Barnetson

Vriend was ground-breaking litigation and this multi-part podcast begins by examining how Canada and Alberta treated members of the LGBTQ2+ community in the decades leading up to 1991 (when Vriend was fire by an Alberta college because of his sexual orientation). The degree of discrimination faced by the LGBTQ2+ detailed in the first episode is, frankly, shocking.

This decision has had significant impacts for labour relations, including the Charter, human rights, immigration, and sex work.

-- Bob Barnetson

Labels:

discrimination,

HRMT322,

HRMT386,

IDRL309,

IDRL320,

immigrants,

LBST325,

LBST415,

LGBT,

public policy,

sex work

Tuesday, April 11, 2023

Complaint over “Mafia-esque” union Xmas cards resolved

An unfair labour practice complaint, alleging Christmas cards sent by a union to the employer’s bargaining team amounted to “Mafia-esque” intimidation, provides insight into the unexpected impact that Alberta’s restrictive picketing laws may have on union pressure tactics during bargaining.

Alberta’s picketing laws

In 2019, the United Conservative Party (UCP) formed government in Alberta. In the summer of 2020, the UCP passed Bill 32: Restoring Balance in Alberta’s Workplaces Act (2020). This act substantially restricted picketing activities by:

- rendering it illegal to obstruct or impede someone from crossing a picket line,

- requiring a union to seek Labour Board permission to engage in secondary picketing, and

- allowing the Labour Board to determine the conditions of any secondary picketing.

These changes effectively rendered legal picketing ineffective and effective picketing illegal. This, in turn, reduced the ability of workers and unions to exert pressure on the employer to move at the bargaining table (which was the intent of the legislation).

Christmas card “intimidation”

Athabasca University Faculty Association (AUFA) served notice to bargain in the spring 2020. By the late autumn of 2021, the employer had not yet provided its monetary proposal and bargaining was stalled. The union began applying pressure in order to generate movement. For example, it filed a bargaining in bad faith complaint with the Labour Board. This proved predictably ineffective due to delay in getting the matter to hearing in a timely way.

The union also began experimenting with the alternative strike tactics that it had developed, in part, because of Alberta’s restrictions on effective picketing. These tactics included choking-off revenue by applying reputational pressure. The first effort was a 12 Days of Christmas meme campaign based on the song “All I want for Christmas is my two front teeth.” Members tweeted these memes at the employer and its bargaining team.

At the end of the online campaign, the most popular meme was then made into a Christmas card. Copies of the card were mailed to homes of the university president and bargaining team co-chairs. In January of 2022, the employer filed an unfair labour practices complaint, alleging the cards were intended to be intimidating, an implicit threat to the safety of the employer’s representatives and their families, and were a “Mafia-esque” tactic.

In April of 2023, the union and the employer settled the unfair. In this settlement, the union agreed, in future, to collect personal information in accordance with Alberta’s privacy legislation (which it is legally bound to do in any case). The union also “acknowledged that those who received the Christmas Cards and members of their families felt that they had been intimidated and harassed.” This settlement is, I think, best read as saving the union the financial cost of the hearing and saving the employer the political cost of losing.

Analysis

The UCP’s changes to Alberta’s labour laws were intended make it more difficult for unions to exert meaningful pressure on employers via picketing that disrupts operations. The desired effect was to attenuate unions’ abilities to make meaningful contract gains.

These changes do not, however, eliminate the need for workers and unions to exert pressure on employers during bargaining. That doesn’t mean these picketing restrictions have no effect on union power. Rather, they just push unions to (1) develop alternative tactics and/or (2) ignore the law and take whatever punishment that entails.

On the surface, mailing Christmas cards to the boss was a very mild alternative pressure tactic. Yet, it triggered a very strong response from the employer. This reaction may have been an effort by the employer to generate some pearl-clutching and internal dissent within the union membership by equating the union with the mob. Or it may have been designed to generate litigation to trade away against the union’s bad faith bargaining complaint.

The tenor of the employer’s complaint, though, suggests real outrage. (I recognize these explanations are not mutually exclusive.) The memes and cards may have driven home for the recipients that collective bargaining can have real world consequences for bosses (just like it always does for workers). It may also have highlighted that the government restricting traditional picketing activities increases the likelihood that unions will expand their tactics to include applying pressure directly on bosses.

While the overall effectiveness of this sort of pressure tactic remains unclear, the employer’s over-reaction to the Christmas card complaint certainly suggests that bosses intensely dislike even the mildest personal pressure and are surprisingly easy, according to their own complaint, to intimidate. This, in turn, tells unions that they should continue to explore this space.

There is significant room to escalate these forms of personally targeted pressure while still staying within the bounds of legal leafletting activity. And the nothing-burger settlement of the employer’s unfair suggests the cost to the union of using these tactics is low.

-- Bob Barnetson

Christmas card “intimidation”

Athabasca University Faculty Association (AUFA) served notice to bargain in the spring 2020. By the late autumn of 2021, the employer had not yet provided its monetary proposal and bargaining was stalled. The union began applying pressure in order to generate movement. For example, it filed a bargaining in bad faith complaint with the Labour Board. This proved predictably ineffective due to delay in getting the matter to hearing in a timely way.

The union also began experimenting with the alternative strike tactics that it had developed, in part, because of Alberta’s restrictions on effective picketing. These tactics included choking-off revenue by applying reputational pressure. The first effort was a 12 Days of Christmas meme campaign based on the song “All I want for Christmas is my two front teeth.” Members tweeted these memes at the employer and its bargaining team.

At the end of the online campaign, the most popular meme was then made into a Christmas card. Copies of the card were mailed to homes of the university president and bargaining team co-chairs. In January of 2022, the employer filed an unfair labour practices complaint, alleging the cards were intended to be intimidating, an implicit threat to the safety of the employer’s representatives and their families, and were a “Mafia-esque” tactic.

In April of 2023, the union and the employer settled the unfair. In this settlement, the union agreed, in future, to collect personal information in accordance with Alberta’s privacy legislation (which it is legally bound to do in any case). The union also “acknowledged that those who received the Christmas Cards and members of their families felt that they had been intimidated and harassed.” This settlement is, I think, best read as saving the union the financial cost of the hearing and saving the employer the political cost of losing.

Analysis

The UCP’s changes to Alberta’s labour laws were intended make it more difficult for unions to exert meaningful pressure on employers via picketing that disrupts operations. The desired effect was to attenuate unions’ abilities to make meaningful contract gains.

These changes do not, however, eliminate the need for workers and unions to exert pressure on employers during bargaining. That doesn’t mean these picketing restrictions have no effect on union power. Rather, they just push unions to (1) develop alternative tactics and/or (2) ignore the law and take whatever punishment that entails.

On the surface, mailing Christmas cards to the boss was a very mild alternative pressure tactic. Yet, it triggered a very strong response from the employer. This reaction may have been an effort by the employer to generate some pearl-clutching and internal dissent within the union membership by equating the union with the mob. Or it may have been designed to generate litigation to trade away against the union’s bad faith bargaining complaint.

The tenor of the employer’s complaint, though, suggests real outrage. (I recognize these explanations are not mutually exclusive.) The memes and cards may have driven home for the recipients that collective bargaining can have real world consequences for bosses (just like it always does for workers). It may also have highlighted that the government restricting traditional picketing activities increases the likelihood that unions will expand their tactics to include applying pressure directly on bosses.

While the overall effectiveness of this sort of pressure tactic remains unclear, the employer’s over-reaction to the Christmas card complaint certainly suggests that bosses intensely dislike even the mildest personal pressure and are surprisingly easy, according to their own complaint, to intimidate. This, in turn, tells unions that they should continue to explore this space.

There is significant room to escalate these forms of personally targeted pressure while still staying within the bounds of legal leafletting activity. And the nothing-burger settlement of the employer’s unfair suggests the cost to the union of using these tactics is low.

-- Bob Barnetson

Monday, February 20, 2023

UNA staffers change bargaining agents

Two weeks ago, 45 staff members at the United Nurses of Alberta (UNA) voted to leave the Steelworkers Union and be represented by the Union of Labour Professionals (ULP), an independent union that the workers formed. The impetus for this change in representation was questions about whether being a part of Steel was the best fit and in the unit's best interests. There were concerns about autonomy and financial transparency, and the catalyzing event was Steel’s perceived interference with the operation of the bargaining unit during a dispute with the employer.

I’d originally planned to use this event as the jumping off point for a discussion about the tension between worker choice and union cartel behaviour and the politics of raiding. But the story itself also proved to be pretty interesting, providing insight into how unions can cause and respond to member dissatisfaction. So I decided to foreground the story.

Background

The Steelworkers represented what I’ll call the professional staff at UNA (as distinct from the clerical and administrative staff) by virtual of a voluntary recognition agreement between Steel and UNA. The skills of the bargaining-unit members (i.e., union staffers) means that the unit is mostly self-sufficient in terms of bargaining, grievances, and other membership servicing tasks. For the most part, then, the unit was left alone by Steel manage its internal affairs (which was sesible for the unit).

During COVID, UNA staffers began working from home. In mid-2021, when UNA called the staffers back to work in the office, the bargaining unit asked UNA to negotiate some flexibility and terms around working from home. UNA said “nope” and referred matters to the next round of bargaining (which was imminent). The workers never did go back to work in the office that year.

Later, bargaining started and, while the unit tried to negotiate some flexible-work language, once again UNA called the workers back to the office. Calling the workers back to the office, according to the bargaining unit, constituted a change in the terms and conditions of work during bargaining, something employers are prohibited from doing.

The bargaining unit filed an unfair labour practice complaint against UNA about this change during the “freeze period”, after telling Steel they were going to, and getting a provisional blessing. Subsequently, a different Steel representative decided the bargaining unit did not have the authority to file an unfair and ordered the bargaining unit to withdraw it. The bargaining unit basically said “yeah, no” and Steel reconsidered.

UNA’s response to the unfair questioned whether the bargaining unit had standing to file an unfair at the Labour Board. Steel’s submission also seemed to question the unit’s standing to file the unfair, which sat poorly with many members of the bargaining unit.

This interference in the unfair crystallized long-term dissatisfaction among many members of the bargaining unit and triggered an organizing drive to replace Steel with an independent union. (The acronym of the Union of Labour Professionals (ULP) is also a commonly used acronym for an unfair labour practice complaint.)

Selecting a Different Bargaining Agent

Alberta’s Labour Relations Code, like labour laws in all Canadian jurisdictions, allows unionized worker to periodically revisit their choice of which union will be their bargaining agent. During these “open periods”, workers can:

The policy rationale underlying open periods is that they hold unions accountable to their members by giving the members the option to periodically revoke their consent to be represented by the union. This option backstops other union accountability mechanisms, such as union’s internal democratic structures (that workers can attempt to use to change union policy) and unions’ duties to fairly represent members during grievance handling.

Steel’s Reaction

When ULP filed a certification application with the Alberta Labour Relations Board, the Steelworkers took steps to try and retain the bargaining unit as a Steel unit. Additionally, some members circulated information to bargaining unit members about the effect of a decertification vote, including that the collective agreement with the employer would be terminated. This is a pretty typical tactic designed to highlight the costs of leaving the union.

This gambit ran into two problems:

The accounts of the meeting I have is that Steel had no coherent presentation and said just wanted to learn about the concerns of the members. Given that a certification had been filed and a vote was likely, this seems like a mis-step: things were well beyond “tell us about your concerns”.

This approach also ceded the initiative to the bargaining unit members, who demanding to see financial statements related to their dues and policies around access to the strike fund. The answers provided by Steel were partial and unsatisfactory and further galvanized support for leaving.

It also opened the door to a member querying whether Steel would be raising objections to the certification application at the Labour Board or would let members democratically decide the matter. The framing of this question neatly backed Steel into a corner (i.e., agree to raise no objections or look anti-democratic) and, in the end, Steel agreed to not raise any objections.

The eventual vote was 29-13 in favour of leaving (about 69%) and the Labour Board recognized the ULP as the new bargaining agent. ULP then served notice on UNA to bargain (or continue bargaining from where Steel left off—that seems to be a bit up in the air at the moment). As the vote suggests, not every member was thrilled with the decision to leave Steel and/or to join an independent union.

The Politics of Raiding

Raiding (when one union tries to recruit members who are already represented by another union) is an extremely contentious issue within the Canadian labour movement. The argument against raiding basically come to down to raiding being divisive (i.e., pitting unions against one another, when they should be cooperating) and wasteful of resources (which could be better spent on servicing members and organizing unrepresented works). There is also concern about the de-stabilizing effect of large-scale raids on the raided unions (which lose dues revenue when they lose members).

Many unions are affiliates of the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) and affiliates are often referred to as being a part of “the House of Labour”. This terminology is essentially a legitimacy claim that throws shade at non-affiliated unions, suggesting that they are in some way suspect (more on that below). The CLC’s constitution bars raiding by its member affiliates. Article 4.5.a states:

In this way, the bar on raiding prioritizes union stability (which is not an inherently bad thing) over worker choice. Workers, of course, retain their statutory right to seek a different bargaining agent during an open period and, at times, CLC affiliates have left the House of Labour (e.g., Unifor in 2018) as a result of raiding (and/or in order to raid).

To navigate these circumstances (wherein no union with “the House of Labour” was likely to agree to represent them, given that Steel was already the recognized bargaining agent), UNA staffers decided to create their own non-affiliated union. This new union may (or may not) decide to affiliate with the House of Labour at a later date.

Non-affiliated unions exist throughout Canada. They are sometimes criticized as being lesser unions, perhaps subject to employer domination and/or unable to provide competent representation and support. Sometimes this criticism seems to ring true, such as with the Christian Labour Association of Canada (CLAC). Other time, such as with the Alberta Union of Provincial Employees, it doesn’t.

In this case, I don’t see much reason for concern. The ULP comprises staffers of a trade union (UNA), who are, by virtue of their professions, able to provide skilled representation. They are also, by virtue of their dispositions, unlikely to be employer dominated. Other union staff in Alberta (such as those who work for the Alberta Union of Provincial Employees) are also represented by independent unions.

If there is a legitimate potential concern about ULP’s ability to serve its members, it might be that the union has not yet accrued significant financial resources to, for example, allow it to provide its members with strike pay. Given the relatively high pay of ULP members, this is unlikely to be a significant barrier to job action, should the union take it. Further, the members of ULP are pretty sophisticated about union matters and would have considered that risk when they decided to cast their vote.

-- Bob Barnetson

I’d originally planned to use this event as the jumping off point for a discussion about the tension between worker choice and union cartel behaviour and the politics of raiding. But the story itself also proved to be pretty interesting, providing insight into how unions can cause and respond to member dissatisfaction. So I decided to foreground the story.

Background

The Steelworkers represented what I’ll call the professional staff at UNA (as distinct from the clerical and administrative staff) by virtual of a voluntary recognition agreement between Steel and UNA. The skills of the bargaining-unit members (i.e., union staffers) means that the unit is mostly self-sufficient in terms of bargaining, grievances, and other membership servicing tasks. For the most part, then, the unit was left alone by Steel manage its internal affairs (which was sesible for the unit).

During COVID, UNA staffers began working from home. In mid-2021, when UNA called the staffers back to work in the office, the bargaining unit asked UNA to negotiate some flexibility and terms around working from home. UNA said “nope” and referred matters to the next round of bargaining (which was imminent). The workers never did go back to work in the office that year.

Later, bargaining started and, while the unit tried to negotiate some flexible-work language, once again UNA called the workers back to the office. Calling the workers back to the office, according to the bargaining unit, constituted a change in the terms and conditions of work during bargaining, something employers are prohibited from doing.

The bargaining unit filed an unfair labour practice complaint against UNA about this change during the “freeze period”, after telling Steel they were going to, and getting a provisional blessing. Subsequently, a different Steel representative decided the bargaining unit did not have the authority to file an unfair and ordered the bargaining unit to withdraw it. The bargaining unit basically said “yeah, no” and Steel reconsidered.

UNA’s response to the unfair questioned whether the bargaining unit had standing to file an unfair at the Labour Board. Steel’s submission also seemed to question the unit’s standing to file the unfair, which sat poorly with many members of the bargaining unit.

This interference in the unfair crystallized long-term dissatisfaction among many members of the bargaining unit and triggered an organizing drive to replace Steel with an independent union. (The acronym of the Union of Labour Professionals (ULP) is also a commonly used acronym for an unfair labour practice complaint.)

Selecting a Different Bargaining Agent

Alberta’s Labour Relations Code, like labour laws in all Canadian jurisdictions, allows unionized worker to periodically revisit their choice of which union will be their bargaining agent. During these “open periods”, workers can:

- take no action and thus remain represented by their existing union,

- have a different union apply to be certified at their new bargaining agent (colloquially called a raid), or

- file a revocation application to become a non-unionized group of workers.

The policy rationale underlying open periods is that they hold unions accountable to their members by giving the members the option to periodically revoke their consent to be represented by the union. This option backstops other union accountability mechanisms, such as union’s internal democratic structures (that workers can attempt to use to change union policy) and unions’ duties to fairly represent members during grievance handling.

Steel’s Reaction

When ULP filed a certification application with the Alberta Labour Relations Board, the Steelworkers took steps to try and retain the bargaining unit as a Steel unit. Additionally, some members circulated information to bargaining unit members about the effect of a decertification vote, including that the collective agreement with the employer would be terminated. This is a pretty typical tactic designed to highlight the costs of leaving the union.

This gambit ran into two problems:

- this was a raid, wherein a new union would inherit the collective agreement, not a decertification, wherein the collective agreement is terminated, and

- the members of the bargaining unit (i.e., union staffers) were savvy enough to know that.

The accounts of the meeting I have is that Steel had no coherent presentation and said just wanted to learn about the concerns of the members. Given that a certification had been filed and a vote was likely, this seems like a mis-step: things were well beyond “tell us about your concerns”.

This approach also ceded the initiative to the bargaining unit members, who demanding to see financial statements related to their dues and policies around access to the strike fund. The answers provided by Steel were partial and unsatisfactory and further galvanized support for leaving.

It also opened the door to a member querying whether Steel would be raising objections to the certification application at the Labour Board or would let members democratically decide the matter. The framing of this question neatly backed Steel into a corner (i.e., agree to raise no objections or look anti-democratic) and, in the end, Steel agreed to not raise any objections.

The eventual vote was 29-13 in favour of leaving (about 69%) and the Labour Board recognized the ULP as the new bargaining agent. ULP then served notice on UNA to bargain (or continue bargaining from where Steel left off—that seems to be a bit up in the air at the moment). As the vote suggests, not every member was thrilled with the decision to leave Steel and/or to join an independent union.

The Politics of Raiding

Raiding (when one union tries to recruit members who are already represented by another union) is an extremely contentious issue within the Canadian labour movement. The argument against raiding basically come to down to raiding being divisive (i.e., pitting unions against one another, when they should be cooperating) and wasteful of resources (which could be better spent on servicing members and organizing unrepresented works). There is also concern about the de-stabilizing effect of large-scale raids on the raided unions (which lose dues revenue when they lose members).

Many unions are affiliates of the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) and affiliates are often referred to as being a part of “the House of Labour”. This terminology is essentially a legitimacy claim that throws shade at non-affiliated unions, suggesting that they are in some way suspect (more on that below). The CLC’s constitution bars raiding by its member affiliates. Article 4.5.a states:

Each affiliate respects the established collective bargaining relationships of every other affiliate. No affiliate will try to organize or represent employees who have an established bargaining relationship with another affiliate or otherwise seek to disrupt the relationship.The CLC constitution also sets out a process for handling efforts by members of CLC-affiliated unions who seek representation by a different union. These provisions basically serve as an impediment to workers changing bargaining agents by bureaucratizing the process and disincentivizing affiliates from seeking to represent such workers.

In this way, the bar on raiding prioritizes union stability (which is not an inherently bad thing) over worker choice. Workers, of course, retain their statutory right to seek a different bargaining agent during an open period and, at times, CLC affiliates have left the House of Labour (e.g., Unifor in 2018) as a result of raiding (and/or in order to raid).

To navigate these circumstances (wherein no union with “the House of Labour” was likely to agree to represent them, given that Steel was already the recognized bargaining agent), UNA staffers decided to create their own non-affiliated union. This new union may (or may not) decide to affiliate with the House of Labour at a later date.

Non-affiliated unions exist throughout Canada. They are sometimes criticized as being lesser unions, perhaps subject to employer domination and/or unable to provide competent representation and support. Sometimes this criticism seems to ring true, such as with the Christian Labour Association of Canada (CLAC). Other time, such as with the Alberta Union of Provincial Employees, it doesn’t.

In this case, I don’t see much reason for concern. The ULP comprises staffers of a trade union (UNA), who are, by virtue of their professions, able to provide skilled representation. They are also, by virtue of their dispositions, unlikely to be employer dominated. Other union staff in Alberta (such as those who work for the Alberta Union of Provincial Employees) are also represented by independent unions.

If there is a legitimate potential concern about ULP’s ability to serve its members, it might be that the union has not yet accrued significant financial resources to, for example, allow it to provide its members with strike pay. Given the relatively high pay of ULP members, this is unlikely to be a significant barrier to job action, should the union take it. Further, the members of ULP are pretty sophisticated about union matters and would have considered that risk when they decided to cast their vote.

-- Bob Barnetson

Labels:

collective bargaining,

IDRL215,

IDRL316,

IDRL320,

labour relations,

LBST200,

organizing,

public policy,

unions

Wednesday, February 15, 2023

Inventive framing of grievances

Typically, when we teach undergraduate students about grievances and rights arbitration, we assume the alleged breach of the contract is obvious and therefore skip over the importance (in practice) of careful grievance framing. This reflects the need to simplify the grievance arbitration (which is pretty complex) in order to not overwhelm students who are new to the process.

As part of a research project, I came across a 2012 case that highlights how the framing of a grievance can be very important to whether or not a union is successful. The decision is:

Canada Safeway Ltd v United Food & Commercial Workers Canada Union, Local No 401, 2012 CanLII 58574 (AB GAA)

You can find the decision on canlii.org by searching the CanLII number (58574). CanLii is an excellent repository of Canadian law.

The basic facts are these:

To start with, the facts were better for a representation grievance than for a termination grievance. The worker stole the chocolate bars in front of a witness. (My first thought reading that as a former grievance officer is “oh yeah, you’re fucked buddy.”) Arbitrators generally view theft in the dimmest of terms (essentially extinguishing the relationship of trust necessary in an employment relationship). Fighting the discipline (despite the possibly mitigating factors) would be a tough slog for the union.

The employer’s error (not providing a union rep) pushes aside the context (i.e., theft) and triggers the fight on much better terrain for the union. Union representation was a clear requirement of the collective agreement and arbitrators generally come down hard on employers who deny worker union representation. In this case, the admission of theft during the interview also opened the worker to potential criminal charges. (If he’d had a union rep, the rep would have terminated the interview and gotten the griever a lawyer.) And the employer’s efforts to remediate the disciplinary process are a de facto admission of the violation.

There is also the issue of available remedy. If the union had won a grievance on the termination, about the best they could have done given the facts was reinstatement (maybe with back pay, but probably without). There is also some hint that the worker did not wish to return to the job.

Under the representation angle, the union sought $10,000 for the worker in damages and $25,000 for the union. If the union won the representation grievance, it stood to attach significant financial and reputation costs to the employer’s conduct (which hopefully would affect the employer’s behaviour going forward).

(There was also the matter of the jurisprudence around theft changing at this time and this was a good case to test whether an older approach, that favoured employers, was still valid. We don’t know if that was in the union’s mind at the time, but maybe it was, since employee theft is a recurring basis of discipline in the retail industry and getting a favourable interpretation of the jurisprudence would be useful to the union in the long term.)

In short, there was a better chance of winning the representation grievances and a much bigger upside to doing so than of winning a termination grievance. This case suggests that experienced union-side advocates, when faced with an apparent violation of a worker’s rights, will often ask themselves “what kind of grievance is most likely to be successful?”

-- Bob Barnetson

Canada Safeway Ltd v United Food & Commercial Workers Canada Union, Local No 401, 2012 CanLII 58574 (AB GAA)

You can find the decision on canlii.org by searching the CanLII number (58574). CanLii is an excellent repository of Canadian law.

The basic facts are these:

- An employee of a grocery store was caught stealing three chocolate bars (valued at $6.37) from the store at the end of his shift. This behaviour is both a violation of employer policy and a crime.

- An employer loss-prevention officer apprehended the worker in the parking lot. The employee was returned to the store and interviewed by security.

- The employer failed to provide the worker with union representation, which was required by the collective agreement. During the interview, the worker admitted the theft.

- When the company learned the interview had taken place without union representation, it discounted all information from the interview, sought to re-interview the member with a union representative present, and, when the union said “yeah no”, the employer terminated the worker based upon the testimony of a witness to the theft.

To start with, the facts were better for a representation grievance than for a termination grievance. The worker stole the chocolate bars in front of a witness. (My first thought reading that as a former grievance officer is “oh yeah, you’re fucked buddy.”) Arbitrators generally view theft in the dimmest of terms (essentially extinguishing the relationship of trust necessary in an employment relationship). Fighting the discipline (despite the possibly mitigating factors) would be a tough slog for the union.

The employer’s error (not providing a union rep) pushes aside the context (i.e., theft) and triggers the fight on much better terrain for the union. Union representation was a clear requirement of the collective agreement and arbitrators generally come down hard on employers who deny worker union representation. In this case, the admission of theft during the interview also opened the worker to potential criminal charges. (If he’d had a union rep, the rep would have terminated the interview and gotten the griever a lawyer.) And the employer’s efforts to remediate the disciplinary process are a de facto admission of the violation.

There is also the issue of available remedy. If the union had won a grievance on the termination, about the best they could have done given the facts was reinstatement (maybe with back pay, but probably without). There is also some hint that the worker did not wish to return to the job.

Under the representation angle, the union sought $10,000 for the worker in damages and $25,000 for the union. If the union won the representation grievance, it stood to attach significant financial and reputation costs to the employer’s conduct (which hopefully would affect the employer’s behaviour going forward).

(There was also the matter of the jurisprudence around theft changing at this time and this was a good case to test whether an older approach, that favoured employers, was still valid. We don’t know if that was in the union’s mind at the time, but maybe it was, since employee theft is a recurring basis of discipline in the retail industry and getting a favourable interpretation of the jurisprudence would be useful to the union in the long term.)

In short, there was a better chance of winning the representation grievances and a much bigger upside to doing so than of winning a termination grievance. This case suggests that experienced union-side advocates, when faced with an apparent violation of a worker’s rights, will often ask themselves “what kind of grievance is most likely to be successful?”

-- Bob Barnetson

Labels:

grievances,

IDRL215,

IDRL316,

IDRL320,

labour relations,

research,

unions

Monday, February 6, 2023

Research: Grievance Arbitration Project

Back in November, I posted a bit about a research project I’m involved with that is looking at grievance-arbitration decisions in Alberta. As of this morning, we’ve coded about 441 decisions by arbitrators (spanning 2006 to 2011) and I’m in a position to talk a bit more about the project and the themes we’re seeing.

When a union and an employer are unable to resolve a disagreement about how the employer has applied the collective agreement (or law, policy, or past practice), they can remit the dispute to an arbitrator for a decision. Arbitration is a form of adjudication akin to the courts. One of the main differences between arbitration and the courts is that, in arbitration, the two parties normally jointly select the arbitrator who will hear the matter (although, sometimes other appointment processes are used).

During the selection process, it is common for a side to internally discuss the merits of proposing or accepting particular arbitrators to hear a matter. This discussion appears premised on the assumption that arbitrators can be (un)sympathetic to certain arguments, evidence, types of grievances, and kinds of grievers. This belief is consistent with a constructivist view of the world, wherein there is infinite stimulus and what one pays attention to and how one interprets that stimulus is driven, in part, by one’s thoughts, beliefs, and expectations.

If the “who you get affects what you get” hypothesis is true, it suggests that identifying patterns in arbitrators’ decision-making can be used to increase the odds of success. This hypothesis (and, if true, the efficacy of various strategies that lever it) is part of what we’ll be examining once we’ve finished coding the dataset (ideally by Christmas 2023, but who knows).

In coding the dataset, we’re assigning the outcome of decisions one of three codes: union win, employer win, or mixed decision. An example of a mixed decision might be a termination grievance. The employer might seek to have the termination upheld, the union might seek to have it overturned and the worker reinstated without penalty, and the arbitrator may eventually decide there was grounds to discipline the worker, but that termination was unreasonable in the circumstances and then substitute some lesser penalty (e.g., a short suspension).

This coding allows us to visually (and statistically, I suppose) represent arbitral decisions like so. Yellow are union wins, green are mixed results, and blue are employer wins.

Note that, in this representation, both the union win and the mixed outcome category result in the worker being better off than they were before the decision. This suggests that looking at the “employer win” category (blue) is a useful way to get a quick and dirty sense of decision patterns.

The graphic above summarizes all decisions. The literature suggests that different types of disputes (e.g., discipline and termination grievances, salary and benefits grievances, grievances addressing seniority, selection, promotion and layoff) will have different win-loss patterns. I have teased apart the data that we have along these lines in the graphic below. Sorry the images are a bit har to read, the lines (top to bottom) are grievances addressing seniority, selection, promotion and layoff, salary and benefits grievances, discipline and termination grievances, and the overall average.

We do seem to see some interesting differences. Note that, in the discipline and termination decisions, the employer typically bears the onus (at least initially) or proving discipline was warranted. In most others kind of grievances, the union bears the onus of proving the grievance should be upheld.

If the “who you get affects what you gets” hypothesis is correct, we should see differences among the decision patterns of different arbitrators. I have presented below a randomly drawn selection of the early data in this regard (carefully anonymized) with the overall average at the top.

What this suggests is that there appear to be large differences in decision outcomes among arbitrators. Two important caveats are worth keeping in mind. This first is that the number of cases in the dataset to date for each arbitrator varies and is, overall, small. Small samples tend to yield swingy numbers, so we shouldn’t jump to conclusions based on a small sample. These differences may attenuate over time as we add cases (although we’re not seeing that yet in the data)

The second is that the facts of each case almost certainly impact the decision of the arbitrator. Our expectation is that, over many cases, differences between cases should attenuate (i.e., wash out) these case-specific differences. Together, these caveats also suggest that eliminating arbitrators with relatively few recorded decisions from the final dataset is likely appropriate.

When we look at arbitrator records on discipline and termination cases (which seem to be the largest single category of cases), we see similarly large differences among arbitrators. I have not visually presented that data, given the small number of cases for each arbitrator.

-- Bob Barnetson

When a union and an employer are unable to resolve a disagreement about how the employer has applied the collective agreement (or law, policy, or past practice), they can remit the dispute to an arbitrator for a decision. Arbitration is a form of adjudication akin to the courts. One of the main differences between arbitration and the courts is that, in arbitration, the two parties normally jointly select the arbitrator who will hear the matter (although, sometimes other appointment processes are used).

During the selection process, it is common for a side to internally discuss the merits of proposing or accepting particular arbitrators to hear a matter. This discussion appears premised on the assumption that arbitrators can be (un)sympathetic to certain arguments, evidence, types of grievances, and kinds of grievers. This belief is consistent with a constructivist view of the world, wherein there is infinite stimulus and what one pays attention to and how one interprets that stimulus is driven, in part, by one’s thoughts, beliefs, and expectations.

If the “who you get affects what you get” hypothesis is true, it suggests that identifying patterns in arbitrators’ decision-making can be used to increase the odds of success. This hypothesis (and, if true, the efficacy of various strategies that lever it) is part of what we’ll be examining once we’ve finished coding the dataset (ideally by Christmas 2023, but who knows).

In coding the dataset, we’re assigning the outcome of decisions one of three codes: union win, employer win, or mixed decision. An example of a mixed decision might be a termination grievance. The employer might seek to have the termination upheld, the union might seek to have it overturned and the worker reinstated without penalty, and the arbitrator may eventually decide there was grounds to discipline the worker, but that termination was unreasonable in the circumstances and then substitute some lesser penalty (e.g., a short suspension).

This coding allows us to visually (and statistically, I suppose) represent arbitral decisions like so. Yellow are union wins, green are mixed results, and blue are employer wins.

Note that, in this representation, both the union win and the mixed outcome category result in the worker being better off than they were before the decision. This suggests that looking at the “employer win” category (blue) is a useful way to get a quick and dirty sense of decision patterns.

The graphic above summarizes all decisions. The literature suggests that different types of disputes (e.g., discipline and termination grievances, salary and benefits grievances, grievances addressing seniority, selection, promotion and layoff) will have different win-loss patterns. I have teased apart the data that we have along these lines in the graphic below. Sorry the images are a bit har to read, the lines (top to bottom) are grievances addressing seniority, selection, promotion and layoff, salary and benefits grievances, discipline and termination grievances, and the overall average.

We do seem to see some interesting differences. Note that, in the discipline and termination decisions, the employer typically bears the onus (at least initially) or proving discipline was warranted. In most others kind of grievances, the union bears the onus of proving the grievance should be upheld.

If the “who you get affects what you gets” hypothesis is correct, we should see differences among the decision patterns of different arbitrators. I have presented below a randomly drawn selection of the early data in this regard (carefully anonymized) with the overall average at the top.

What this suggests is that there appear to be large differences in decision outcomes among arbitrators. Two important caveats are worth keeping in mind. This first is that the number of cases in the dataset to date for each arbitrator varies and is, overall, small. Small samples tend to yield swingy numbers, so we shouldn’t jump to conclusions based on a small sample. These differences may attenuate over time as we add cases (although we’re not seeing that yet in the data)

The second is that the facts of each case almost certainly impact the decision of the arbitrator. Our expectation is that, over many cases, differences between cases should attenuate (i.e., wash out) these case-specific differences. Together, these caveats also suggest that eliminating arbitrators with relatively few recorded decisions from the final dataset is likely appropriate.

When we look at arbitrator records on discipline and termination cases (which seem to be the largest single category of cases), we see similarly large differences among arbitrators. I have not visually presented that data, given the small number of cases for each arbitrator.

-- Bob Barnetson

Labels:

grievances,

IDRL215,

IDRL316,

IDRL320,

labour relations,

research,

statistics,

unions

Wednesday, January 25, 2023

Notice of termination vs severance

One of the challenges of teaching students about interpreting collective agreements is the effect of clauses is often very hard to know because they can interact with other clauses in the collective agreement as well as other regimes of employment law. As part of a research project, I came across a 2011 decision that is a fun read about termination notice and severance pay.

The decision is:

Canadian Energy Workers Association v ATCO I-Tek Business Services Ltd, 2011 CanLII 81659 (AB GAA)

You can find the decision on canlii.org by searching the CanLII number (81659). CanLii is an excellent repository of Canadian law.

The basic facts are these:

The employer’s argument (again, loosely) was that the entitlements are mutually exclusive and applicable in different circumstances and this the benefits do not compound. Reading the provisions as complementary creates an excessive benefit for the workers.

I won’t spoil the ending for you. The panel’s decision flows from an interesting exploration of the purpose of each of the rights in the contract, the language used, and the effect they have for different employee groups. This decision is a relatively simple example of this kind of inquiry, that occurs in many contract interpretation grievances.

The ultimate decision (that I found to be surprising) highlights how parties can negotiate provisions that each finds acceptable without mutually working through the actual operation of those provisions. This can reflect the nature of bargaining (where ambiguous language may be a strategy to, for example, defer a fight), the complexity of language (which can give rise to legitimately different interpretations), and the impact of practical constraints (e.g., bargaining is often done under the gun by very tired people who sometimes make errors of omission).

-- Bob Barnetson

The decision is:

Canadian Energy Workers Association v ATCO I-Tek Business Services Ltd, 2011 CanLII 81659 (AB GAA)

You can find the decision on canlii.org by searching the CanLII number (81659). CanLii is an excellent repository of Canadian law.

The basic facts are these:

- The employer was outsourcing a significant number of positions and this resulted in significant number of terminations.

- The collective agreement gave the affected workers rights to (1) working notice (or pay in lieu of notice) under Article 30 and (2) severance under Article 32 and a Letter of Agreement.

- The union argued that the permanent workers were entitled to benefit from both sets of rights; the employer argued that workers were only entitled to severance.

- (There was a second issue around a worker signing a release that isn’t really all that interesting.)

The employer’s argument (again, loosely) was that the entitlements are mutually exclusive and applicable in different circumstances and this the benefits do not compound. Reading the provisions as complementary creates an excessive benefit for the workers.

I won’t spoil the ending for you. The panel’s decision flows from an interesting exploration of the purpose of each of the rights in the contract, the language used, and the effect they have for different employee groups. This decision is a relatively simple example of this kind of inquiry, that occurs in many contract interpretation grievances.

The ultimate decision (that I found to be surprising) highlights how parties can negotiate provisions that each finds acceptable without mutually working through the actual operation of those provisions. This can reflect the nature of bargaining (where ambiguous language may be a strategy to, for example, defer a fight), the complexity of language (which can give rise to legitimately different interpretations), and the impact of practical constraints (e.g., bargaining is often done under the gun by very tired people who sometimes make errors of omission).

-- Bob Barnetson

Thursday, January 5, 2023

How OHS sentences are determined

Many labour-side practitioners assert that the financial penalties levied against employers that violate occupational health and safety rules are so low that they do not serve as a deterrent to future violations by the same or a different employer (basically, they are just the cost of doing business). In some jurisdictions, employers can be subject to modest tickets or administrative penalties for violations. Where an employer has done something serious, they can also be subject to prosecution under OHS legislation.

Pleading or being found guilty can result in fines being assessed by the court within whatever range is set in the legislation. Section 48 of the Alberta’s OHS Act, for example, sets the maximum penalty for a first-time violation at $500,000 (plus a 20% victim surcharge) and/or not more than six months of imprisonment. (In theory, employers can also be charged under the Westray provisions of the Criminal Code, but that basically never happens. Similarly, jail time for an OHS prosecution is almost never imposed.)

There were 11 (or maybe 12, see below) convictions in Alberta under the OHS Act in 2022:

A recent Saskatchewan Court of King’s Bench sentencing decision following a workplace incident that left a worker paralyzed is helpful in understanding the factors used when the Court’s determine fine levels. The maximum fine available to the judge in Saskatchewan was $1.5 million. Paragraph 12 sets out the factors commonly used to assess penalties.

[10] R v Westfair Foods Ltd., 2005 SKPC 26, 263 Sask R 162 [Westfair Foods] is a seminal case in Saskatchewan for the sentencing of corporations for OHS violations causing injury. At paragraph 38, Whelan J. distilled the essential principles from the case law and academic works as follows:

i. The primary objective of regulatory offences is protection and in the context of occupational health and safety legislation, it is the protection in the workplace of the employee and the general public.

ii. The sentencing principle which best achieves this objective is deterrence and while deterrence may be regarded in its broadest sense and includes specific deterrence, general deterrence is a paramount consideration.

iii. There are numerous factors, which may be taken into account and the weight attributed to each will depend upon the circumstances of each case. The following is not an exhaustive list of factors that may be considered, but they are likely relevant to most occupational health and safety offences:

An interesting part of the discussion was the court’s efforts to set the fine at a level that served as a deterrent but was not so high that the owners of the corporation just walked away from the corporation (and thus the fine goes unpaid). The impact of limited liability corporations to shield owner-operators from some or all of the consequences of the corporation’s actions is a recurring bugbear for enforcing employment laws.

Perhaps, rather than further raising fine maximums (which seems to have a modest impact on actual fine levels) and perhaps fine minimums, legislatures might consider piercing the corporate veil to hold directors personally liable for unpaid OHS fines?

-- Bob Barnetson

Pleading or being found guilty can result in fines being assessed by the court within whatever range is set in the legislation. Section 48 of the Alberta’s OHS Act, for example, sets the maximum penalty for a first-time violation at $500,000 (plus a 20% victim surcharge) and/or not more than six months of imprisonment. (In theory, employers can also be charged under the Westray provisions of the Criminal Code, but that basically never happens. Similarly, jail time for an OHS prosecution is almost never imposed.)

There were 11 (or maybe 12, see below) convictions in Alberta under the OHS Act in 2022:

- Precision Trenching Inc pled guilty to a 2018 trench collapse fatality and paid a fine of $275k.

- Insituforms Technology Inc pled guilty to a 2019 serious injury and paid a fine of $100k.

- Emcom Services Inc pled guilty to a 2019 serious injury and was fined $86k. (This conviction appears twice on the list, but I think that is an error).

- Amyotte’s Plumbing & Heating Ltd pled guilty to a 2019 fatality and was fined $170k.

- Joseph Ogden pled guilty to a 2019 fatality and was fined $80k.

- Trentwood Ltd pled guilty to a 2020 fatality and was fined $150k.

- The Town of Picture Butte pled guilty to a 2020 serious incident and was ordered to pay $87k in creative sentencing.

- Kikino Metis Settlement pled guilty to a 2020 serious incident and was ordered to pay $8.5k in creative sentencing.

- McCann’s Building Movers Ltd pled guilty to a 2020 fatality and was fine $320k.

- Polytubes 2009 Inc pled guilty to a 2020 serious injury and were ordered to pay $100k in creative sentencing.

- Cross Borders Consulting Ltd pled guilty to a 2020 fatality and was fined $324k.

A recent Saskatchewan Court of King’s Bench sentencing decision following a workplace incident that left a worker paralyzed is helpful in understanding the factors used when the Court’s determine fine levels. The maximum fine available to the judge in Saskatchewan was $1.5 million. Paragraph 12 sets out the factors commonly used to assess penalties.

[10] R v Westfair Foods Ltd., 2005 SKPC 26, 263 Sask R 162 [Westfair Foods] is a seminal case in Saskatchewan for the sentencing of corporations for OHS violations causing injury. At paragraph 38, Whelan J. distilled the essential principles from the case law and academic works as follows:

i. The primary objective of regulatory offences is protection and in the context of occupational health and safety legislation, it is the protection in the workplace of the employee and the general public.

ii. The sentencing principle which best achieves this objective is deterrence and while deterrence may be regarded in its broadest sense and includes specific deterrence, general deterrence is a paramount consideration.

iii. There are numerous factors, which may be taken into account and the weight attributed to each will depend upon the circumstances of each case. The following is not an exhaustive list of factors that may be considered, but they are likely relevant to most occupational health and safety offences:

- the size of the business, including the number of employees, the number of physical locations, its organizational sophistication, and the extent of its activity in the industry or community;

- the scope of the economic activity in issue - the value or magnitude of the venture and any connection between profit and the illegal action;

- the gravity of the offence including the actual and potential harm to the employee and/or the public;

- the degree of risk and extent of the danger and its foreseeability;

- the maximum penalty prescribed by statute;

- the range of fines in the jurisdiction for similar offenders in similar circumstances;

- the ability to pay or potential impact of the fine on the employer's business;

- past diligence in complying with or surpassing industry standards;

- previous offences;

- the degree of fault (culpability) or negligence of the employer;

- the contributory negligence of another party;

- the number of breaches - were they isolated or continued over time;

- employer's response - reparations to victim or family - measures taken and expense incurred so as to prevent a re-occurrence or continued illegal activity, and;

- a prompt admission of responsibility and timely guilty plea.

[25] … For Courts to give "the legislative intent its full effect" we cannot be bound to prior sentencing ranges that do not reflect the Legislature's view of the gravity of the offence and society's increased understanding of the severity of the harm arising from the offence (see paras. 108-109). An upward departure from prior precedents is appropriate to arrive at a proportionate sentence.As set out in Paragraphs 24 and 25, the Saskatchewan judge fined King Stud $126k (effectively one year of net proceeds) to be paid of a time period to be determine later. The range of fines

[24] A total penalty (fine and surcharge) of roughly one year’s net proceeds to the principals of the corporation, with time given to pay, is a proper balancing of all of the factors in this case - including the fact that, other than its early guilty plea, virtually none of the Westfair Foods factors are in King Stud’s favour, and some of them (such as its compliance record before and after this incident) are strongly against it.It’s hard to know if this fine will cause the employer (which had an appalling safety record before this entirely foreseeable injury) to alter its behaviour or serve as a deterrent to other employers. I’m pretty skeptical. These were bad actors who got busted after the fact for yet another fall protection violation.

[25] Such a fine will be a very significant penalty to the principals of the corporation but should not be so debilitating as to cause the collapse of King Stud. Will it be extremely uncomfortable for them for several years? Undoubtedly; but not nearly so uncomfortable as the rest of Dawson Block’s life will be for him, as a result of their actions or inaction.

An interesting part of the discussion was the court’s efforts to set the fine at a level that served as a deterrent but was not so high that the owners of the corporation just walked away from the corporation (and thus the fine goes unpaid). The impact of limited liability corporations to shield owner-operators from some or all of the consequences of the corporation’s actions is a recurring bugbear for enforcing employment laws.

Perhaps, rather than further raising fine maximums (which seems to have a modest impact on actual fine levels) and perhaps fine minimums, legislatures might consider piercing the corporate veil to hold directors personally liable for unpaid OHS fines?

-- Bob Barnetson

Labels:

HRMT322,

HRMT323,

IDRL308,

IDRL320,

injured workers,

injury,

public policy,

safety

Wednesday, November 16, 2022

Statutory law versus the collective agreement, a fun example

When we teach HR and LR students about the web of rules that regulate employment, we often focus our attention on the various sources of rules (e.g., common law, statutory law, contracts and collective agreements). This reflects that students need to (1) build a mental framework in order to understand how employment law operates and (2) develop some foundational knowledge of what the rules actually are (e.g., what are the basic rules around firing someone?).

One of the topics that gets glossed over in this sort of introduction is that, sometimes, what the law means (in practice) isn’t clear. Or, at least, an employer and worker/union might have a different interpretation of what the law required or permits. This can reflect legitimate differences of opinion, differing interests, and, sometimes, apparent conflict between rules from different sources of law. In the interests of time (and understanding that a survey course is just an introduction), we tend to wave this complexity aside with “disputes are remitted to an adjudicative body for resolution.”

Sometimes, it is worthwhile having a look at a case to see just how this adjudication works. As part of a research project, I came across an interesting arbitration decision from 2009 that is a fun read. The decision is:

Edmonton Space & Science Foundation v Civic Service Union 52, 2009 CanLII 90156 (AB GAA)

You can find the decision on canlii.org by searching the CanLII number (90156). CanLii is an excellent repository of Canadian law.

The basics facts are these:

This decision is a good example of how employment-law sausage is actually made when the parties can’t agree and when there are multiple sources of rights that may conflict.

-- Bob Barnetson