You can read a summary here but the gist is major studios are trying to cheapen work in order to gain a greater portion of the surplus value generated by labour.

The bosses’ strategy, at least with respect to the Writers Guild of America, appears to be simply starving out the workers. According to Vanity Fair, the bosses expect writers to run out of money by October and, once the workers are facing homelessness, they will resume negotiations and press for concessions. Starving workers until they give up is an age-old employer tactic.

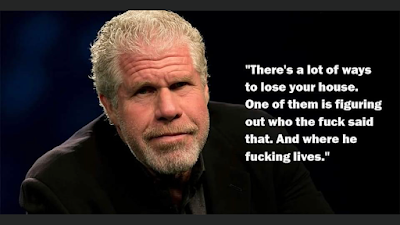

Actor Ron Perlman, in a now deleted video, reacted to the bosses’ plan this way:

That hasn't always been true, though. Underlying every job action is the potential for violence. Often it has been used by bosses to bust a strike. But, occasionally, workers will destroy the bosses’ property or attack them directly. The post-war labour compromise in Canada has attenuated this risk, in part by strictly regulating strikes and strike behaviour.

But, when the bosses refuse to negotiate in good faith (or the system looks otherwise completely rigged against them), worker commitment to obeying labour law may fray because it is no longer in their interest to do so.

We most often see this dynamic play out in wildcat strikes. But worker frustration doesn’t have to be channelled in that direction. A worker or smnall group of workers could, as Perlman hints, just destroy a boss’s house or yacht or factory or mine or whatever.

It is worthwhile for both bosses and workers to pay attention to the potential for this kind of behaviour as they strategize how to bargain. Bosses who decide to play hardball, may be opening Pandora’s box. And worker may be overlooking a significant source of leverage by discounting alternatives to picketing.

-- Bob Barnetson

The bosses’ strategy, at least with respect to the Writers Guild of America, appears to be simply starving out the workers. According to Vanity Fair, the bosses expect writers to run out of money by October and, once the workers are facing homelessness, they will resume negotiations and press for concessions. Starving workers until they give up is an age-old employer tactic.

Actor Ron Perlman, in a now deleted video, reacted to the bosses’ plan this way:

The motherfucker who said we’re gonna keep this thing going until people start losing their houses and apartments — listen to me motherfucker.

There’s a lot of ways to lose your house. Some of it is financial. Some of it is karma. And some of it is just figuring out who the fuck said that — and we know who said that — and where he fucking lives.Perlman’s statement got quite a lot of media play because it is out of step with most people’s understanding of how contemporary strikes play out (basically people stop working and walk around with signs until the boss decides to negotiate). Suggesting that bosses might face violent, real-world consequences for trying to get even richer by economically destroying workers’ lives is pretty uncommon these days.

There’s a lot of ways to lose your house. You wish that on people? You wish that families starve while you’re making 27 fucking million dollars a year for creating nothing? Be careful motherfucker. Be really careful. Because that’s the kinda shit that stirs shit up.

That hasn't always been true, though. Underlying every job action is the potential for violence. Often it has been used by bosses to bust a strike. But, occasionally, workers will destroy the bosses’ property or attack them directly. The post-war labour compromise in Canada has attenuated this risk, in part by strictly regulating strikes and strike behaviour.

But, when the bosses refuse to negotiate in good faith (or the system looks otherwise completely rigged against them), worker commitment to obeying labour law may fray because it is no longer in their interest to do so.

We most often see this dynamic play out in wildcat strikes. But worker frustration doesn’t have to be channelled in that direction. A worker or smnall group of workers could, as Perlman hints, just destroy a boss’s house or yacht or factory or mine or whatever.

It is worthwhile for both bosses and workers to pay attention to the potential for this kind of behaviour as they strategize how to bargain. Bosses who decide to play hardball, may be opening Pandora’s box. And worker may be overlooking a significant source of leverage by discounting alternatives to picketing.

-- Bob Barnetson