Of note was the direction given PSE institutions by the Minister of Advanced Education to drop masking requirements. My position was that the Minister did not have the authority to order institutions to not comply with the OHS Act (which obligates them to take all reasonably practicable steps to protect workers from occupational hazards, such as COVID).

Yesterday, a Court of King’s Bench decision dropped that is relevant. In it, the judge notes that the Minister of Education, who prohibited school boards from requiring mandatory masking, had overstepped her authority. The nub of it was that the Minister needed to issue such direction in the form of a regulation, rather than just make a statement. Absent a regulation, the Education Act empowers school boards to make their own policies.

Presumably, PSE boards of governors would be in the same situation as school boards since section 59 of the Post-Secondary Learning Act (which addresses the power of PSE boards) is very similar to the language in the Education Act. That is to say, boards are not enjoined from implementing mandatory masking (or vaccination) policies simply because the Minister of Advanced Education said so.

If cabinet enacts a regulation (under the Regulations Act) enjoining boards from implementing masking policies, we them to consider whether such a regulation trumps the requirement set out in section 3 of the Occupational Health and Safety Act that boards, as employers, must take all reasonably practicable steps to protect the health and safety of workers. This includes an obligation, under section 9 of the OHS Code to control hazards.

This is all mostly an academic matter for two reasons.

First, COVID-related policies in Alberta PSEs seem to fall clearly into the “minimizer” camp and decisions about protections are simply left to individuals. Basically, there is no political will among campus administrators to protect workers or students from COVID.

Individualizing OHS issues (e.g., “you can wear a mask if you like”) ignore that masking is most effective when it is uniformly adopted. This makes intuitive sense: if everyone masks, we have two layers of protection against aerosol transmission versus one layer under the current "wild west" policy approach. This approach also ignores that ventilation (something only an employer can address) can reduce transmission.

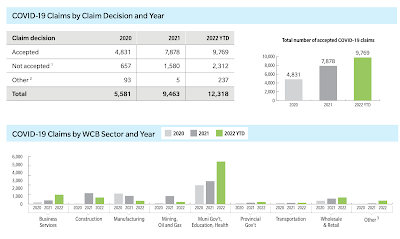

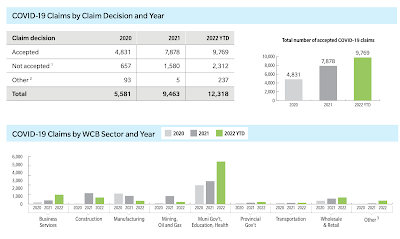

Second, as I wrote about in September, Alberta’s OHS officers seem unwilling to engage with the hazard of aerosol transmission. This seems like an enormous dereliction of duty given Alberta’s workplace COVID stats (the screen cap below is from October 28, 2022--note the sectoral distribution of COVID claims...). Clearly COVID is a serious workplace hazard in Alberta. The only sector that seems to still recognize that is health care.

-- Bob Barnetson

Second, as I wrote about in September, Alberta’s OHS officers seem unwilling to engage with the hazard of aerosol transmission. This seems like an enormous dereliction of duty given Alberta’s workplace COVID stats (the screen cap below is from October 28, 2022--note the sectoral distribution of COVID claims...). Clearly COVID is a serious workplace hazard in Alberta. The only sector that seems to still recognize that is health care.

-- Bob Barnetson