Fairness at Work Declines

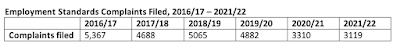

The number of employment standards complaints filed were up by about a third in 2022/23. Complaints tend to reflect a fraction of overall violations; most workers don’t bother reporting things like wage theft.

This is an interesting reversal of a long-term decline in employment standards complaints.

Notably, the time to begin an investigation tripled and the time to resolve a complaint doubled. This has long been a bugbear in the employment standards system. The report asserts this reflects increasing volume and complexity.

The number of complaints investigated with signs of human trafficking jumped from 102 in 2021/22 to 208 in 20223/23.

The number of administrative penalties issued to employers dropped from 3 in 2021/22 to zero in 2022/23.

Safety: Losing the Will to Enforce

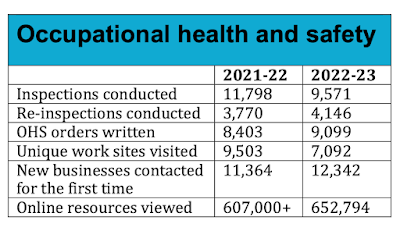

Worksite inspections plus re-inspections totalled 13,717 in 2023/23, down 12% from 15,569 in 2021/22. If you look later in the report for some context, this is about 6% fewer inspections/re-inspections than in 2018/19 (14,590), which was the last full year when the NDs were in power. At this rate, the inspection cycle is theoretically about once every 15 years (give or take).

About 80% of inspections were the results of complaints while the remaining 20% were targeting industries with safety problems. There were 1207 proactive inspections in 2022/23 resulting in 1725 orders issued. This is down from 2021/22, with 2100 inspections and 2548 orders. I couldn't find any historical data in this to provide context.

The number of investigations (e.g., of injuries) dropped by 60%, from 2245 in 2018/19 to 888 in 2022/23.

Orders written were up slightly over 2021/22 to 9099. This may be good (more enforcement) or may be bad (more violations occuring)—hard to say. If you look at 2018/19, there were 16,680 orders issued.

Ticketing of violators was down. There were 27 tickets with a total value of $11,280 issued in 2022/23. This is slightly fewer than in 2021/22 (32 tickets, $11,500). This reporting leaves out important context. If you look at 2018/19, there were 479 tickets issued.

Administrative penalties were also down. There were 17 penalties worth $62,025 issued in 2022/23. This is notably fewer than in 2021/22 (37, $314,250).

Convictions were also down, with 2022/23 seeing $1,740,750 in fines assessed. This is down from $1,919,000 in 2021/22. There was no reporting of the number of convictions but a hand count suggests the number is stable the last few years at around (hand-waggle) 10 per year, down from more than 20 in 2018/19.

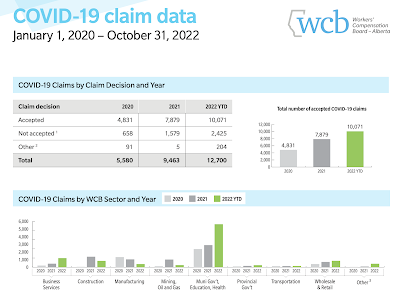

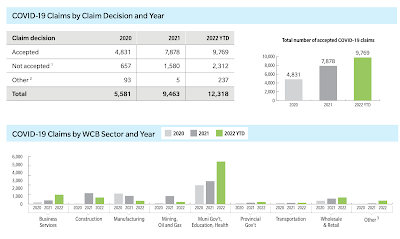

Injury Rates are Up: Yeah, it’s mostly COVID.

The lost-time claim rate rose for at least the seventh straight year. Much, but not all, of this increase is due to COVID-19 injuries.

The disabling injury rate (lost-time plus modified work) is also up. Again, much but not all of the increase is due to COVID injuries.

The absence of meaningful government protocols related to aerosol spread put responsibility for these COVID-related increases squarely on the shoulders of government.

Interestingly, the absolute number of accepted fatalities is down to 120 (from 136). There is no real analysis of that change. It could be the result of changes in the workforce composition. It could also just be random variation (small numbers tends to be swingy).

Analysis

Overall, it looks like the government continues to lose the will and/or capacity to meaningfully enforce workplace safety rules under the UCP. Not surprisingly, the rate of injury has risen, likely because workplaces are more dangerous.

There has also been an uptick in complaints about employment standards (basically wage theft). This could be caused by more workers knowing to and being willing to come forward. I’d guess, though, that this reflects employers knowing it is open-season on workers under the UCP and, thus, stealing wages more frequently.

-- Bob Barnetson